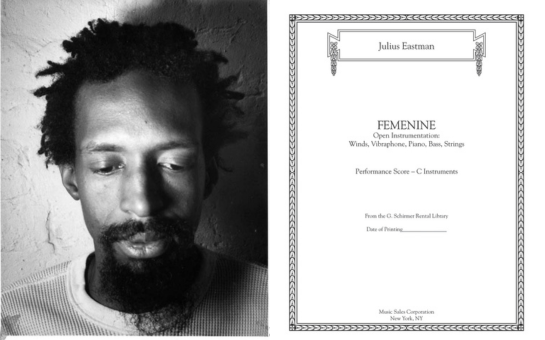

- Julius Eastman

Femenine (1974)

- Music Sales Corporation (World)

richard valitutto, editorial advisor

- open instrumentation (winds, marimba/vibraphone, sleigh bells, piano, bass)

- 1 hr 15 min

Programme Note

Performance note

Julius Eastman conceived nearly all of his works for people he knew personally, his close friends and colleagues. The most prominent of these collaborators were the S.E.M. Ensemble of which he was also a member, and for whom Eastman originally composed and performed Femenine and its more famous predecessor Stay On It (1973).

Like many of his works, the score to Femenine should not by any means be understood as a complete set of instructions or detailed description for performance. Nevertheless, a scan of the manuscript score — the only one surviving for Femenine — is likely the only document that was used to perform the work in his lifetime. This is not unusual: across his prolific compositional output, Eastman used indeterminacy and improvisation as critical components to realize and perform his works, as well as instructions and compositional decisions communicated verbally in rehearsal. In other words, of the handful of works that are not completely lost, having only a recording or only a score still gives a substantially incomplete picture.

Thankfully, in this regard Femenine is a rare exception, making performances of Femenine after Eastman’s death especially possible. In addition to this manuscript score, there exists one recorded performance of the work, with Eastman at the piano. Made in Albany, NY in 1974, this recording was commercially released in 2016 by the frozen reeds label. It can be assumed that the players all performed from photocopies of Eastman’s handwritten score in performance, and also received verbal instructions and physical cues from him during rehearsals and — as can be heard on the recording — in performance.[1]

The first priority in preparing this performance edition of Femenine was to reflect the archival manuscript’s staff and text notation as closely as possible. Any editorial explanations or clarifications are in smaller font size or in square brackets; round brackets are simply used to indicate parenthetical remarks. When preparing Femenine for performance, it is encouraged both to consult the now-plentiful recordings of the work and to study Eastman’s other large-scale works. Moreover, a successful, satisfying performance of Femenine requires an understanding of Eastman’s overall body of work and its influences, which reflect the ways that improvisation and other approaches radicalized concert music performance in the 1970s.

For most of the 70s and early 80s, Eastman worked with a myriad of creative colleagues in the Center for the Creative and Performing Arts at SUNY-Buffalo, as well as in New York City’s kaleidoscopic Downtown arts scene, and in concert halls, museums, and galleries across the United States and Europe. Notable influences on Eastman during this time would have included the oracular modal jazz solos of Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane, Terry Riley’s modular works grounded in both Western and North Indian Classical training, John Cage’s numerous stopwatch-controlled pieces and theatrical works, the conceptual works and improvisations of Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich’s process pieces for his ensemble, FLUXUS happenings, and performing with both Meredith Monk’s glossolalic vocal ensemble and in Arthur Russell’s mutant disco studio experiments as Dinosaur L.

Throughout his lifetime and career, Eastman was renowned for his multi-faceted virtuosity, premiering and performing numerous works of his own and by many others as singer, pianist, and dancer. In interviews, he often illustrated his points by referring to an extremely wide range of other composers and styles, both historical and contemporary, and these anecdotes reflect his diverse experiences with all music as conceptual, philosophical, social, political, and performative.

Femenine is the earliest, most substantial example of what Eastman would later concretely call “Organic Music,” a compositional approach in which he thoroughly and methodically generated large-scale, multi-sectioned works from minimal musical materials to explore multiple discursive trajectories. In the case of Femenine, one can understand the entire work to be grown from the seeds of the main vibraphone motive, a relentless 13-beat ostinato using only two pitches but employing three distinct rhythmic articulations: tremolo, syncopation, and sustain.

The scant musical instructions can thus be seen as an invitation — both generative and provocative, even. Performers can and should feel empowered to approach the score as an exactly sufficient starting point for creation and performance. According to Eastman’s closest collaborators for Stay On It, he gave the players exactly as much as was required to have the maximum effect, including on-the-fly verbal and gestural instructions. While introducing Stay On It to an audience in Glasgow in 1974, Eastman said that as a composer he relied on his players’ “innate musical abilities” to realize the work in performance — collaboration beyond rote execution.

That same year, Eastman premiered Femenine in Albany with a large ensemble comprised of members of the S.E.M. Ensemble as well as local players. A year later, Eastman presented Femenine in New York City at The Kitchen with a different, substantially smaller ensemble. It is quite likely, then, that Femenine’s evolving, seemingly “incomplete” manuscript is nevertheless more written-out than we can imagine Stay On It ever was. (Eastman and his close colleagues in the S.E.M. Ensemble were the only performers of Stay On It in his lifetime, giving dozens of performances across the US and Europe.) If one looks at the manuscripts to the works from the late 70s, culminating with Gay Guerrilla, his notational techniques for this unique Organic Music for open ensemble are refined and clarified, as one might expect. When rehearsing and performing Femenine, I have found it helpful to have had experiences with these later works especially.

For it is through performance, which includes the performance acts of both practice and rehearsal, that Eastman’s works are best developed, realized, and understood. Performers of Femenine and other Eastman works like it will discover that preparing the work with colleagues in an open-minded, experimental, and democratic environment is advantageous, and even necessary, far more than any score study or private “shedding” can afford on their own.

— richard valitutto (editorial advisor)

[1] On the manuscript score a number of handwritten additions appear, most of them seem likely to be from someone other than Eastman, especially when compared with those that clearly are his. Those clarifications, addenda, and edits which are obviously Eastman’s have all been incorporated in this performing edition — some those which are likely not written by Eastman have been with discretion.

Media

Reviews

…“Femenine” breaks free of the template of classic minimalism. Riley’s “In C” and Steve Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians” shimmer and flow, dancing a little off the ground. “Femenine” stomps, strides, and storms.

…meditative, kaleidoscopic, eventually ecstatic…

Throughout, Eastman as interpreted by this troupe provides a sense of playfulness and joy that is sometimes missing from serious music. As a result, Femenine works on multiple levels and holds up to multiple listenings. To that point, after my first pass through this hour-plus epic, I immediately started it again for a second listen.

Femenine comes out on June 18 from New Amsterdam Records. Do not hesitate.

Femenine is also where Wild Up is starting its Eastman recording venture. The work’s irresistible pulsations and spirited improvisations ideally suit this group…

Discography

Julius Eastman Vol. 1: Femenine | Wild Up

- LabelNew Amsterdam Records

- ConductorChristopher Rountree

- EnsembleWild Up

- Released18th June 2021

Julius Eastman – Femenine

- LabelSub Rosa

- Catalogue NumberSR501

- EnsembleEnsemble 0 & AUM grand ensemble

- Released19th November 2020

Julius Eastman – Femenine

- LabelFrozen Reeds

- Catalogue Numberfr6

- EnsembleS.E.M. Ensemble

- Released1st August 2016

More Info

- Julius Eastman in 2025: New Edition of Femenine, Bicoastal Exhibits, Dancing to the Fullest

- 23rd January 2025

- G. Schirmer and Wise Music Group are pleased to announce a new performance edition of Femenine, a seminal work of open-form minimalism composed by Julius Eastman in 1974.

- Kyle Marshall's Julius Eastman Trilogy

- 19th November 2024

- Around the United States, Kyle Marshall Choreography continues to unveil their powerful Julius Eastman Trilogy, which honors love, liberation, queerness, and the legacy of Eastman and his music.

Located in the UK

Located in the UK

Located in the USA

Located in the USA

Located in Europe

Located in Europe