Emil de Cou became Pacific Northwest Ballet's Music Director and Principal Conductor at the start of the 2011-2012 season. He was associate conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra, participating in a wide range of NSO performances and events following his Wolf Trap debut in 2000.

He debuted at Carnegie Hall as guest conductor for the New York Pops and has also conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Pops, and the Colorado Symphony Orchestra. He was Principal Pops Conductor for the San Francisco Symphony and served as musical consultant for NASA collaborations, including "Salute to Apollo, the Kennedy Legacy" at the Kennedy Center.

In 1985, Mikhail Baryshnikov hired de Cou to conduct American Ballet Theatre and in 1994, he joined the staff of San Francisco Ballet; he conducted San Francisco Ballet's production of Lar Lubovitch's Othello for "PBS Great Performances: Dance In America." He has also conducted New York City Ballet, Suzanne Farrell Ballet, National Ballet of Canada, Netherlands Dance Theatre, Hong Kong Ballet, and National Ballet of Holland, among others.

Emil de Cou was born in Los Angeles and studied at the University of Southern California.

In Conversation with Emil de Cou

Emil de Cou

What drew you to conduct for dance and how did this opportunity present itself?

I have always been interested in conducting for ballet because of all the great music written for dance, starting with the Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky ballets that I first heard in Fantasia (1940) when I was still in high school. From there my love grew when I saw my first live performance of ballet with American Ballet Theatre in Los Angeles in 1979 (The Rite of Spring) and watching "Live from Lincoln Center" on PBS since we did not have a major company in Southern California at the time. My first chance to conduct for ballet was in 1985 when I guest conducted the National Ballet of Holland and the Netherlands Dance Theater. It was a dream come true and from that experience there was no turning back.

The desired attributes for succeeding as a conductor of dance are unique. Did you have a mentor guiding you through the specifics of conducting for dance?

It's not something you learn in conducting school. In fact, conservatories don't offer specific courses in dance conducting. They teach you high and mighty things like Mahler and Bruckner, but they should also teach how to conduct Nutcracker and American in Paris. My greatest mentors in learning conducting for dance was ABT's wonderful rehearsal pianist, Henrietta (Gena) Stern, a wonderfully talented Russian pianist and one of the kindest people I've ever known. I would sit next to her at the piano in our huge studios at 890 Broadway and she would tell me what the steps were called and when to wait and more importantly when not to wait for dancers. My other mentor was the great English ballerina Georgina Parkinson who was the ballet master at ABT when I was on staff. I still hear her telling me to "stop following the toe-shoes, it is so B-O-R-I-N-G." With Georgina (and many other British dancers) and with George Balanchine music always came first.

One of the most important challenges and skills for dance conductors is the ability to keep a steady tempo without becoming inexpressive or mechanical. You cannot rely on spontaneous rubatos or accelerations to create excitement or pathos. Would you agree, it's not the conductors role to make the dancers comfortable, but to make them look good in the choreography?

Twyla Tharp told me (half joking maybe) "never listen to the dancers" anytime she joined me in the pit during stage rehearsals years ago. While you don't ever want the dancers to be uncomfortable you do sometimes want to give them, through the music, the energy they need to thrill and excite an audience. It is one thing to be rehearsing in a studio and another to experience the rush of being on stage, flooded with spotlights, when the curtain goes up and you are in front of a full house. It's about tempo — it is necessary core ability for all musicians to have a strong sense of rhythmic pulse.

Do you believe concert/symphonic conductors could learn something from dance maestros?

It is important to remember that before people became specialists, conductors directed all musical art forms, ballet, opera, and symphony. Pierre Monteux, who conducted the premieres of Petrushka and The Rite of Spring among many other ballets, was one of the most famous conductors of his day. It is important to be well rounded in your education and experience as a musician because it informs everything that you do. Can you really conduct Appalachian Spring without knowing Martha Graham and Aaron Copland's storyline behind the music? It would be like conducting Salome without knowing what the words meant. It's a good idea to be curious about everything related to a piece of music and not just the notes on the page: when it was written, what the world was like at the time, what the composer was like as a person and performer, who it was written for and how was it first performed. Sometimes getting your head out of a music book is the first best way of learning what it is really all about.

Choreography can also help an audience make sense of a difficult score such as Stravinsky's works. Your thoughts?

For example, with some of George Balanchine ballets, audiences respond immediately to the wit and tension of Balanchine. On its own a work like Agon can seem rather dry. People listen with their eyes. Although Stravinsky denied it later, he originally said that all of his ballets were written with a strong story underneath the music. While The Rite of Spring does work as a piece of abstract music, the complete Petrushka and Firebird no longer do (sadly neither do Daphnis and Chloe, The Prodigal Son, and Coppélia). All those pieces were until the 1970s standard orchestral repertoire, but without the storyline in your audience's head the music is lost. It's much like trying to program the complete North by Northwest or Vertigo by Bernard Herrmann without the film. But with the film the performances sell out. I remember the first time The Wizard of Oz was performed with live orchestra at Wolf Trap in 2006, we were not quite sure how it would be received. It then turned out to be the start of this new way of concert presentation.

What do you feel is trick to navigating the right balance between pragmatic considerations and "pure" music and slavishly following a dancer's every move?

Dancers never look good if the music sounds bad. If a work is performed in a less than musical way it reflects on the person on stage. Even with Minkus's Don Quixote or La Bayadere the work has to make musical sense. It is more compelling to do so with Mendelssohn, Delibes, or Copland. As much in ballet that the audience listens with their eyes they also see with their ears. Distorted music does no one any favors and all you have to do is watch old performances of Nureyev and Fonteyn, or Baryshnikov and Cynthia Harvey and you'll see how very musical those wonderful dancers are at all times.

Because orchestra rehearsals with dancers are so scarce, conductors spend hours in the studio and collaborate closely with rehearsal pianists, dancer's rehearsal directors, and various casts. You successfully continue to conduct for multiple ballet companies and differing productions. How do you navigate the specifics of multiple choreographic versions and multiple casts in each company?

When I guest conduct for a symphonic concert, I arrive the evening before the first rehearsal and probably stay around three or so days. With dance you have to spend days or weeks in the studio before the first orchestra rehearsal takes place. You must get to know the choreographers, dancers, stage managers, and lighting designers. Each company is different but what stays the same is your relationship that you develop with each dancer, knowing them as a person and as a performer. When I have multiple casts, my score is usually covered in multicolored Post-it Notes to keep everyone straight.

Do you have differing pre-show rituals for full length ballets and one act works, whether they be narrative or abstract works?

I have the same ritual for each performance no matter how many times I've conducted a certain ballet. I usually show up in my dressing room about a half an hour before the show (no dinner since that makes you too sleepy) and then go through each act page by page before I go down to the pit. It is a way of refocusing the mind and closing off all the other things that went on that day. It is meditative in a certain way.

Can you share you experience with the challenges of performing with varying auditoriums, dancers, audiences and orchestras?

There are always challenges with various venues, size of the orchestra, stage, the acoustics of the theaters, etc. One thing that I have learned in over 30 years of conducting here and around on tour is that you have to be flexible and learn from people who have worked in those places before you. I rely of colleagues who know various theaters and orchestras for advice since each situation is unique. I learned a great deal with our national and international tours with American Ballet Theatre since I had the chance to conduct major works repeatedly and discovered quickly what to do and as important what not to do with your rehearsal time and in performance.

In my work with NASA over the past nearly 20 years I've discovered the amazing power of combining the arts and sciences. Our first collaboration with NASA and the National Symphony Orchestra (where I was associate conductor for some years) was on Holst's The Planets, long before it was common to perform the work with imagery and video. Leonard Nimoy was the narrator and to this day I have never heard an audience yell so loudly at a symphony concert as when he walked on stage and flashed the "Vulcan salute" to the audience! I remember him saying backstage that the arts and sciences begin the same way. It all starts as a fantasy. Be it a Beethoven symphony or landing on the moon — it is all about imagining something that does not yet exist. That is why I love theater in collaboration with music so much and why movie concerts have become so wildly popular. When you combine music with either dance or film you tap into a deeper part of the human psyche that either art form on its own cannot do.

Being Music Director/Principal Conductor with Pacific Northwest Ballet affords watching dancers progress through their ranks and enjoying the fruition of building finely synched rapport. Does this allow for added "risk-taking" in both classical and contemporary productions?

Seattle in particular and the West Coast in general have a strong following for newness, be it in social constructs, trends, and innovation in technology and in the arts. John Cage and Merce Cunningham at Cornish College, Seattle's own Mark Morris, Bakersfield native Twyla Tharp, not to mention the birth of popular radio, movie, television and the Internet explosion. Things seem to move from West to East, and, in the case of John Cage, Allan Watts, and John Adams, from the Far East to the American West and then onto Europe and the world. For human beings and the arts to thrive you must have an open mind. We all crave what is good and new in life, and the arts do as well. There are some less progressive places where audiences only want to attend a performance in the same way you would flip through an old book of snapshots and memories. Just look at what the big new releases on Netflix are — I don't think it's reruns of the 1960's sitcom "My Mother the Car" (but then again you never know).

Reviews

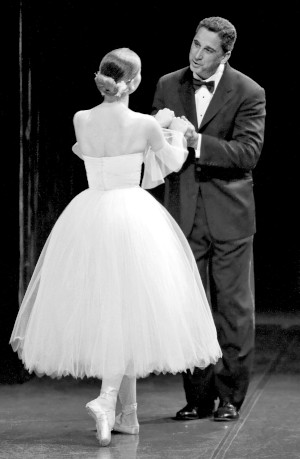

Emil de Cou © Angela Sterling

"Beethoven's Egmont Overture, the centerpiece, made the most of the orchestra's warm, generous sound and de Cou's sense of phrasing and character." — Ronny Reich, Washington Post

"First, an apology all too relevant for the subject of this review. Earlier this week, in my review of the Suzanne Farrell Ballet's season in Washington, I neglected to mention either the Kennedy Center's orchestra or its conductor, Emil de Cou. Both show standards higher than those we are used to hearing in New York; Mr. de Cou may now be the finest ballet conductor in America." — Alastair Macaulay, The New York Times

Watch

Virtual Concert: The NSO Pops Celebrates NASA, April 24, 2020