- Franz Waxman

The Spirit of St. Louis: Ireland (1957)

- Warner Chappell Music Inc (USA and Canada only)

- 3(I,II:pic;III:pic,[tsx]).2(II:ca).3[=4][III:tsx]+bcl.2(II:cbn)/4.3.3.1/timp.2perc/hp[=2].pf(cel)[=2]/str

- 4 min 20 s

- 6th February 2026, McCallum Theatre for the Performing Arts, Palm Desert, CA, United States of America

- 7th February 2026, McCallum Theatre for the Performing Arts, Palm Desert, CA, United States of America

Programme Note

“There’s land. Living green earth. What land? Where am I? It’s Dingle Bay. It’s…Ireland! ”

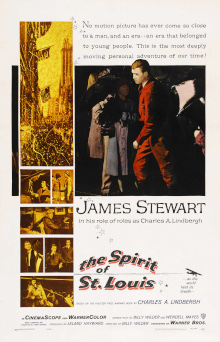

The veteran actor, Jimmy Stewart, once said that, in the movies, he was always striving to produce believability with little “pieces of time.” And believability was crucial in Stewart’s portrayal of legendary flier Charles Lindbergh and the “man against the elements” story of his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic. In The Spirit of St. Louis (1957), directed by Billy Wilder, Stewart is carried aloft, not only by his replica of Lindbergh’s single engine monoplane, but the heroic, emotional score of Franz Waxman. So much depended on Waxman because of the limited use of dialogue and action, as the story unfolds against the long overwater flight.

Wilder’s star was really too old to play Lindbergh. Stewart was 48, Lindbergh 25 when he flew into history. But this was more then an actor playing a role. Growing up in Indiana, Pennsylvania, where his father ran a hardware store, Stewart once recalled how he put a model of Lindbergh’s plane in the window of his dad’s store, hanging betweeen a Woolworth building replica and one of the Eiffel Tower. Young Stewart, 19, would check the teletype at the Indiana Evening Gazette for Lindbergh’s progress, then run across the street to the store to move the model closer to France. By the time he filmed The Spirit of St. Louis, there was another affinity with Lindbergh. By 1941, Stewart, a bona fide movie star, had obtained his private and commercial pilot’s license and eight months before Pearl Harbor, reported for induction into the Army…as a private. When he was discharged four years later, he was Colonel in the U. S. Army Air Corp, and had flown twenty combat missions on B-24s over Nazi-occupied Europe. A strong propoent of airpower, he enthusiastically took part in films that showed off the Air Force, like Strategic Air Command (1955), or, as narrator of the drama about edge-of-space test flying, X-15 (1961.)

Early in The Spirit of St. Louis project, there was an effort to aquire the rights to the little-known Lindbergh’s Flight cantata by Paul Hindemith and Bertholt Brecht. That fell through and Wilder again turned to his friend Waxman. Wilder knew he needed strong musical accompaniment for his story because, as he said, “Mr. Lindbergh was a very difficult man to make into a movie hero. He had become a Scandanavian, Viking hero, without flesh and blood. [There were] no characters fighting against Lindy, no conflict, just one man against the elements.”

Waxman felt that “film music must make its point immediately because it is heard only once by an audience that is unprepared and didn’t come to the theater to hear film music anyway.” The “Ireland” cue finds Stewart still over the Atlantic after the long night of fighting off sleep. Suddenly two fishing vessels appear, then tiny islands, and at last, the coast of Ireland. Waxman uses the film’s basic “In Flight” theme and then places it counter to an Irish jig for Stewart’s vocally jubilant landfall at Dingle Bay. (It’s one of Stewart’s “pieces of time.”) As pilot and plane skim the masts of fishing vessels, villages, and an ancient Irish castle, Waxman celebrates the triumph of the moment, signaling the movie’s audience that the hardest part is over and Paris lies just ahead.

A big fan of this film is director Steven Spielberg, who spoke glowingly of Wilder and Waxman in Cameron Crowe’s book, Conversations with Wilder. Crowe said Spielberg was able to describe in great detail the in-flight sequence and then hummed Waxman’s score note for note, including the Irish elements Waxman incorporated.

It is interesting how the passage of time has placed greater emphasis and recognition on Waxman’s contribution to the movie. In the original 1957 soundtrack recording, the notes on the back of the LP (the long-playing record), are mainly about Lindbergh the man. There is only one paragraph given over to the movie itself and one sentence about the music. However, that sentence is factual in stating that “in the music…we are able to experience again some of the great emotions evoked by this epic story.”

— Jim Brown

Located in the UK

Located in the UK

Located in the USA

Located in the USA

Located in Europe

Located in Europe