Takemitsu at 100: “an ocean that has no west and no east”

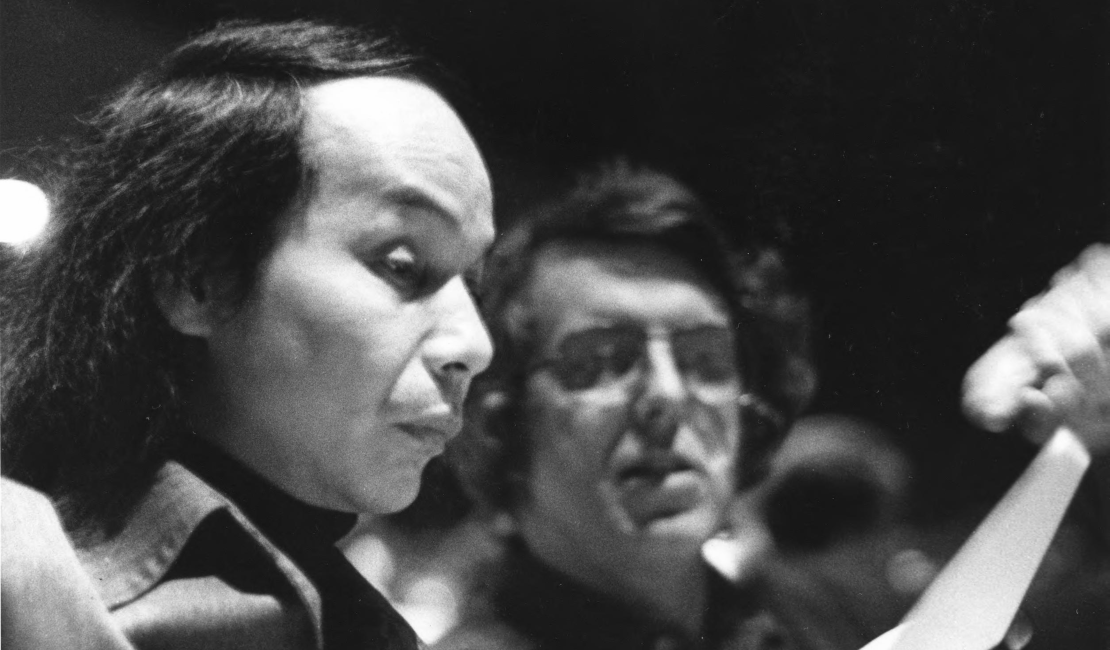

Tōru Takemitsu (left) and Roger Reynolds (right)1

A true artist is a person who, descending to the bottom of his inner mineshaft, reveals himself like a piece of unrefined ore […] music is song and song is love.

— Tōru Takemitsu2

To prepare for the upcoming centenary of Tōru Takemitsu in 2030, Edition Peters and Wise Music Group are pleased to present a brief guide to our small but vital catalogue of symphonic works by this iconic Japanese composer.

Music of Tree (1961) - large orchestra, 17 minutes

Like all of Takemitsu’s works published by Edition Peters, Music of Tree belongs to what many scholars have considered his second, “modernist” stylistic period. It is one of Takemitsu’s earliest orchestral pieces, clearly influenced by Anton Webern in its brief, distilled gestures and moments of repose. Unusually for Takemitsu, the piece even contains a moment of true serial writing, with a 12-tone row composed out into a retrograde canon at measure 29; fittingly, the row is constructed of two overlapping octatonic subsets, allowing the composer to nod towards Webernian technique while incorporating a scalar collection that was to become characteristic of his sound.3 Perhaps most importantly in the context of Takemitsu’s artistic development, Music of Tree already demonstrates the composer’s deep interest in timbre — of what musicologist Peter Burt has called an emphasis on “sound” over “syntax,” or a prioritization of the details of each sonic experience over abstractable form or pitch relationships.4

November Steps (1967) – shakuhachi and biwa with orchestra, 20 minutes

Commissioned for the New York Philharmonic’s 125th anniversary, November Steps was Takemitsu’s first large-scale work combining traditional Japanese instruments with Western ones.5 He described this task as arduous but ultimately rewarding: “The attempt to bring together Japanese instruments with a Western orchestra was so difficult that many times along the way I felt like giving up. To try to blend the two drastically different forms of music seemed virtually impossible […] however difficult though it was, I think that making the attempt was very worthwhile because what resulted somehow liberated music from a certain stagnation and brought to music something distinctly new and different.”6

The result encompassed a range of sonic resources. The shakuhachi and biwa parts often remain distinct from the orchestral writing, employing graphic notation for their solo sections and fundamentally divergent sound worlds from the symphonic instruments; as John Caps observes, November Steps “find[s] its voice by surrendering the effort to affiliate the Eastern guest instruments with the Western orchestra.”7 Despite this, Takemitsu laces beautiful points of congruence, such as pedal glissandi on the harp dovetailing into microtonal inflections by the soloists, and Bartok pizzicati on the cellos emulating the “slap” gestures from the biwa repertory.8

Takemitsu’s symmetrical seating plan uses the stereo field to create “orchestral enlargements” of the biwa and shakuhachi sound.9 Dense, apparently chromatic textures are built from modal and scalar harmonic structures, including a chord built out of the pentatonic scale represented by the piano’s black keys (which would become a kind of trademark sonority for the composer in the decades to come).

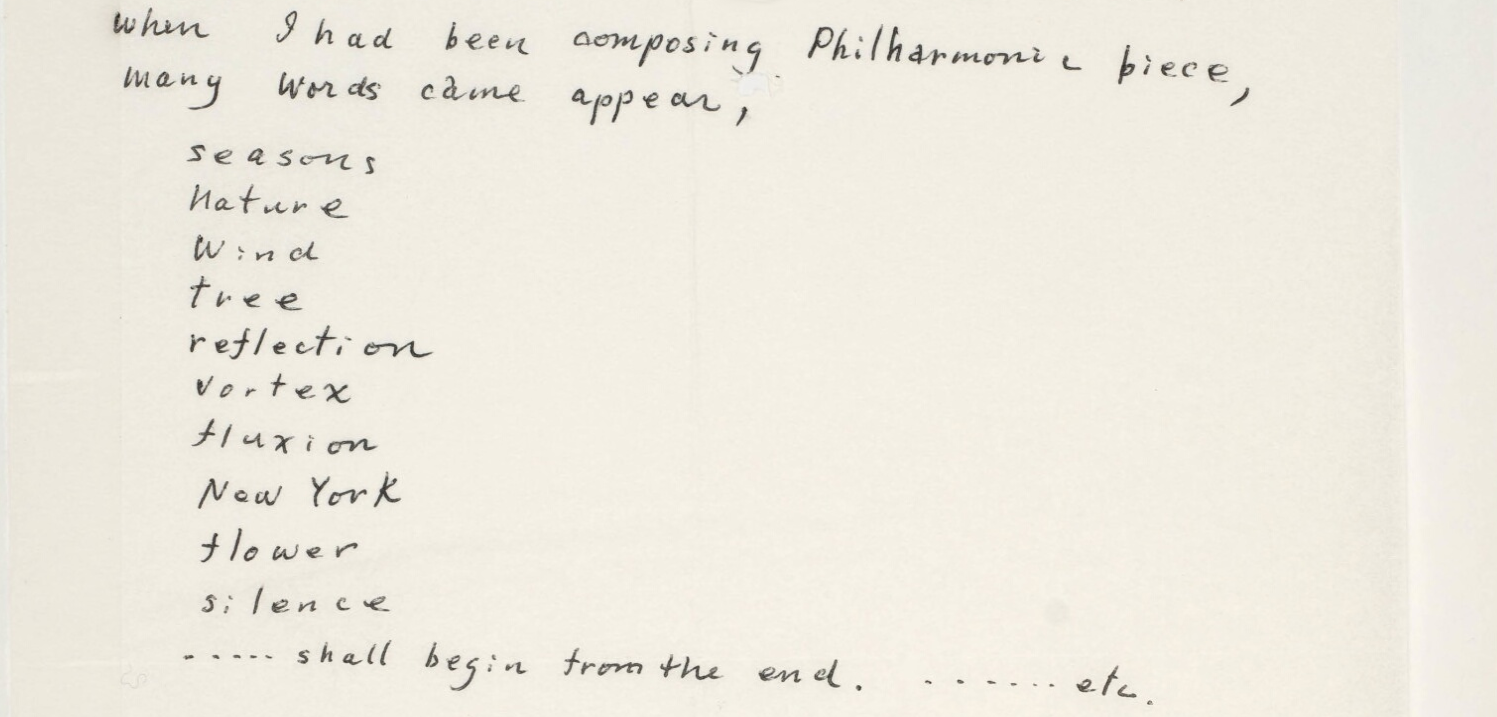

One could spend years investigating this monumental piece through such analytic frameworks. In many ways, though, this would run counter to both Takemitsu’s own mode of talking about his music — which always tended towards the poetic — and what Burt and other scholars have wisely considered analysis’ “impotence to explain the whole of [Takemitsu’s] creative thinking.”10 In the end, perhaps it is best to consider the piece in light of the evocative list of words Takemitsu sent to the New York Philharmonic’s program note writer in 1967: to listen and to experience this remarkable work in the context of the rich environments around us.

Excerpt of 1967 letter from Takemitsu to musicologist/program note writer Edward Downes.

From the New York Philharmonic Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives and reproduced with their kind permission.11

Green (1967) – orchestra, 6 minutes

By 1967, Takemitsu’s self-professed “enslavement” to Webern was abating as he reached a new comfort with the symphonic medium.12 Green was written around the same time as November Steps, and it is a kind of sister piece to the longer work. Of the two, it is the more immediately accessible; Takemitsu beautifully integrates melodic writing with his characteristic focus on timbre. The end is sweet — almost neo-Romantic in tone before ultimately moving into something more Debussyian. (Takemitsu in fact took the scores to Debussy’s Prélude à l'Après-midi d'un faune and Jeux to the mountain house in which he composed Green and November Steps, and he himself applied the terms Romantic and neo-Romantic to his later music as he valued their connotations of intense self-expression.13) In many ways, Green foreshadows Takemitsu’s turn in the final two decades of his life towards a less avant-garde style: one filled with simpler textures and more overtly beautiful harmonies, but with just as intense a focus on the details of instrumental sonorities.

Asterism (1969) – piano and large orchestra, 12 minutes

Asterism seems to be a name with a dual meaning: the titular word can mean either a group of stars, or a printer’s mark consisting of three asterisks placed in a triangular shape. Peter Burt reads these twin definitions as a hint towards a kind of Augenmusik (“eye music”) in which visual markings are interpreted in notation — in this case, the opening triplet theme may gesture towards the printer’s mark or the layout of a constellation.14 This kind of translation of celestial patterns onto notation forms the core technique of Atlas Elipticalis by John Cage, which Takemitsu heard when he traveled with Cage a few years earlier in 1964. Perhaps, then, this is a gesture that reveals one of many “aftershocks” of the “Cage shock” Takemitsu experienced when he first heard Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra in 1961.15 Cage and Takemitsu’s list of aesthetic sympathies is certainly long: similar philosophies of sound and silence as a continuum, an interest in graphics, rejection of traditional formal patterns, and more. Still, unlike Cage’s ultimate turn towards indeterminacy and minimization of his own role in directing his listeners’ experiences, Takemitsu turns these ideas towards fiercely expressive ends. In Asterism, delicate orchestral sounds move into active, restless textures of winds and metallic percussion, then ultimately into what Roger Dettmer has called “the full-blown and fiery crescendo of white noise which forms the anguished and ultimately ecstatic climax.”16

About Tōru Takemitsu

Fellow Edition Peters composer Roger Reynolds was a close friend and colleague of Takemitsu and notes that “Takemitsu’s life [was] rife with intense and widely divergent experience.”

As a young man in Japan’s Chinese colony of Manchuria, Takemitsu was drafted into a labor gang to construct Japanese army camps as a young teenager during World War II. His personal reaction to the war-time climate of Japanese imperialism was a hatred of his country and its culture. He avidly consumed the music of American composers such as Copland, Sessions, and Piston, then later Berg, Webern, Debussy, and Messiaen as he worked for the U.S. Armed Forces and taught himself to compose after the war. He remained largely self-taught throughout his life, eschewing both higher-level formal training and any teaching position. By his 20s, his works were being broadly performed, and he had co-founded the multimedia artistic group Jikken Kōbō, which was heavily influenced by the Western avant-garde. A chance encounter with Stravinsky in 1958 brought him a Koussevitsky commission, which later premiered under Copland’s baton in the US and helped him build his position as an internationally recognized composer heard across concert halls and in a number of film scores.

Takemitsu ultimately embraced aspects of Japan’s cultural and intellectual heritage that colored his unique — and uniquely sensitive — approach to space, form, timbre, and musical gesture.17 By the 70s and 80s, he had emerged as both a true believer in the power of serious cultural exchange and a unique voice that aimed towards a unity of expression that drew on both “Western” and “Eastern” aesthetics but ultimately rose above such a dichotomy.18 Though he was characteristically modest and expansive in his attitude towards his work (“The quantity of work I have composed so far comes to no more than a few hours, so short as to be only a moment compared to the total number of hours since I began to possess consciousness as a person,” he wrote in 1974), he deeply influenced both colleagues like Reynolds and Cage and some of the most important composers of the following generations.19 From Tan Dun to Kaija Saariaho (the Water Concerto and Six Japanese Gardens are both dedicated to Takemitsu), orchestral audiences to piano students, Takemitsu’s visionary music-making reverberates today. As Reynolds writes of his friend’s music: “The argument is never concluded. The implications continue to resonate. The ripples continue to spread outwards — in time, in memory —"

1 Marc Lieberman: Toru Takemitsu and Roger Reynolds, Mandeville Auditorium, UCSD, 1970. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200029042/

2 Tōru Takemitsu, “Watashi no Hōhō — Myūjikku Konkurēto nit suite” [My Method — Concerning musique concrète”, Bijutsu Hihyō 1 (1956), 70; qtd in Peter Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, Music in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, 96.

3 Peter Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 74.

4 As Burt observes, “Takemitsu’s keen ear for timbral subtleties had been evident from the very earliest phase of his career, but from around the beginning of the 1960s onwards his ability to conjure a wealth of differentiated sonorities entered on a new phase of refinement, one which was to continue unabated through the remainder of his life.” Peter Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 80.

5 Theorists such as a Yayoi Everett have termed this a strategy of “syncretism.” While it was a successful, innovative strategy in November Steps, it was not one Takemitsu would go on to employ often afterwards — whether because of monumental task involved notationally and compositionally or because of his ever-increasing search for a unity of “Western” and “Eastern” expression. Yayoi U. Everett, “From Exoticism to Interculturalism: Counterframing the East–West Binary.” Music Theory Spectrum 43, no. 2 (2021), 332. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27141632.

6 Tōru Takemitsu, “Contemporary Music in Japan,” Perspectives of New Music 27, no. 2 (1989), 201-202.

7 John Caps, “Toru Takemitsu: ‘A Gardener, West of Eden’” in Crisis music: the life-and-times of six twentieth-century composers. Sussex Academic Press, 198. https://doi.org/10.3828/9781789761467.

8 Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 116.

9 For discussion of spatialization across stereo field, see Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 114. For discussion of orchestral enlargements of the soloists’ sound, see Lewis Cornwell, “Tōru Takemitsu’s November Steps,” Journal of New Music Research 31, no. 3 (2002), 213.

10 Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 3.

11 Tōru Takemitsu, letter to Edward Downes, August 28, 1967, ID: 561-08-006, New York Philharmonic Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives, https://archives.nyphil.org/index.php/artifact/f252f470-31fd-487a-91cb-3837525c33fe-0.1/fullview#page/4/mode/2up.

12 Tōru Takemitsu, Ki no Kagami, Sōgen no Kagami [Mirror of Tree, Mirror of Grass], Tokyo, Shinchō Sha, 1975, 29; qtd. in Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 60.

13 Roger Reynolds and Tōru Takemitsu, “Roger Reynolds and Tōru Takemitsu: a Conversation,” Musical Quarterly 80, no. 1 (1996), 70.

14 Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 106.

15 In an obituary essay for Cage written over three decades after he heard Concert for Piano and Orchestra, Takemitsu wrote that he could “still feel the shock of hearing that piece.” Tōru Takemitsu, Confronting Silence, Berkeley, California: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995, 137.

16 Roger Dettmer, sleeve notes for the original RCA recording (RCA SB 6814).

17 Though scholars such as Peter Burt have demonstrated that Takemitsu engaged with Japanese musical materials well before his “Cage shock,” complicating the story of Cage as the primary factor in Takemitsu’s gradual appreciation for elements of Japanese aesthetics, the fact remains that Takemitsu himself credited Cage with this role. He remarked in 1992: “I must thank John Cage, because he shifted my attention to the positive sides of Japanese culture; I had long regarded ‘Japan’ and anything related to it as things that are supposed to be rejected.”

18 On the subject of cultural exchange, Takemitsu wrote in 1988: “In this age, we face problems which are both political and economic in nature. To free ourselves from such problems I think the most important thing is the ability to understand each other deeply through cultural exchange […] Each country must take care to avoid concealing itself within its own shell.” Toru Takemitsu, “Contemporary Music in Japan.” Perspectives of New Music 27, no. 2 (1989), 198. Takemitsu’s desire for a unity of expression that sidestepped conceptions of Eastern and Western aesthetics is amply demonstrated by the quote borrowed for the title of this feature: Takemitsu’s professed wish to “swim in the ocean that has no west and no east.” Shinji Saitō and Maki Takemitsu (eds), Takemitsu Tōru no Sekai [The World of Tōru Takemitsu], Tokyo: Shūei Sha, 1997, 148; qtd in Burt, The Music of Tōru Takemitsu, 234.

19 Sumi Adachi, Roger Reynolds, Tōru Takemitsu, “Mirrors.” Perspectives of New Music 30, no. 1 (1992), 36. https://doi.org/10.2307/833284.